I have often thought that from the point of view of the driver, the dashboard may be the one part of the street rod that is most viewed. You watch the graceful rising arc of the tachometer as your foot sinks deeper into the throttle and you are appreciative of that tachometer—valuable information may keep an expensive engine in one piece. The back of your head is someone else’s problem. It’s not like you have to stare at it for hours on end or use it for critical gear changes. So you can leave its destiny up to the femme with the buzzin’ clippers and call it good. Not so with the dashboard of the street rod. You will stare that thing down on long road trips and need to consult it during gear changes and illicit top-speed testing. It had better be right. It had also be pretty.

Back to my 35 Dodge pickup. It came with a dashboard just like all cars and trucks. The word “dashboard” was originally used to describe the wooden or leather “board” carriage makers attached to the front of carriages to prevent mud and rocks from being splashed (or “dashed”) onto drivers and their passengers by the horses that pulled them about. In essence, dashboards served as mud flaps for horses’ hooves. Absent the horses, builders of horseless carriages found that board to be a convenient location for gauges that displayed various bits of useful information like how fast am I traveling. By 1935 the dashboard was highly evolved. Better a dashboard than a mud flap in your modern car. Won’t you agree?

But that old mud flap wasn’t always the epitome of style. The red dashboard featured above is from a 35 Dodge pickup—not mine but a good one. It shows some factory design effort to please the eye but is frankly quite utilitarian. And that’s generally okay with pickup owners. However, that very same year Dodge had a more visually pleasing dash for buyers of its upscale sedan models. I found one.

35 Dodge pickup—not mine but a good one. It shows some factory design effort to please the eye but is frankly quite utilitarian. And that’s generally okay with pickup owners. However, that very same year Dodge had a more visually pleasing dash for buyers of its upscale sedan models. I found one.

This was more like it and I decided to jettison the original dashboard in favor of something with more “dash” and “flare”. I had scoured the country for a Dodge sedan dashboard. This is quite easily done online. I found a parts yard (we used to call them “junk” yards) that had acres of mostly Dodge, DeSoto, Chrysler and Plymouth cars. A sedan dashboard in good shape was on offer. There was no glove box door but I reasoned I could find one elsewhere. And eventually I did, albeit with some difficulty and for a princely sum.

This was more like it and I decided to jettison the original dashboard in favor of something with more “dash” and “flare”. I had scoured the country for a Dodge sedan dashboard. This is quite easily done online. I found a parts yard (we used to call them “junk” yards) that had acres of mostly Dodge, DeSoto, Chrysler and Plymouth cars. A sedan dashboard in good shape was on offer. There was no glove box door but I reasoned I could find one elsewhere. And eventually I did, albeit with some difficulty and for a princely sum.

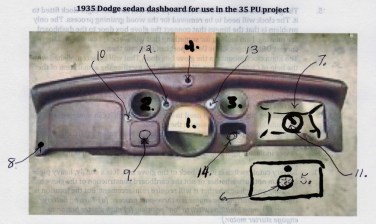

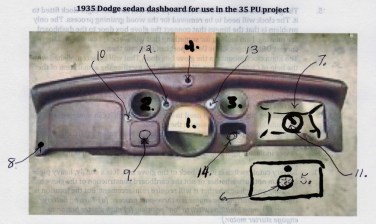

I saw great potential in the new dashboard. It had a huge central hole for the very cool looking speedometer and a couple of holes where planned air conditioning vents could find a home, and other smaller ones where light and wiper switches could be fitted. The glove box door would be the ideal location for the original Elgin clock to be placed. A machinist cut the exact sized hole. By original I mean it isn’t a fake Elgin, not that it was ever found in a 35 Dodge pickup.

The glove box itself, the box part not the door, will be custom made from aluminum rather than cardboard because it will house a battery cutoff switch. That switch can shut off all power from the battery. An ignition key won’t be used and it will take three steps to actually start the vehicle (battery on, ignition on, press starter button). I guess that’s reasonably secure on the strength of the assumption that most thieves can’t follow more than two consecutive steps or won’t think to look in the glove box for the battery cutoff switch.

The more I thought about the new dashboard, the more complicated it became.

Finally I promised Ralph that before I left to come to Geneva I would lay out the whole dashboard design in a separate document. You see the schematic here.

When it came time to fit the new dashboard in its proper front and center location we discovered that it wasn’t the same length as the original. I would have thought the pickup would be narrower but not so. Ralph welded a half inch of new metal on each end of the dash to make it fit just so.

An old flywheel was used to take the place of a steering wheel when Ralph fit the new, but still rough, dashboard in place inside the bare cab. The trial fit looks good. The plan is to paint the dashboard in pepper white–the secondary color for the truck. The firewall is the same color and the contrast appears to be pleasing. We’ll hear what the critics say later.

Not sure where he found that old seat but Ralph wanted to be sure about how things were lining up inside. I’ll have more to say about the steering column later. It goes straight through, not beneath, the left-hand side of the dash.

As work on the “new” dashboard proceeds, you will notice a couple of things. One, the dash is sanded and primered and sanded again–many times. Two, air conditioning vents have been added in round holes where square holes (see above) were found originally. Three, the hole for the dash mounted steering column has been cut in precisely the right place. From there the steering column enters the steering drop mechanism. I’ll save a complete explanation of that piece of engineering marvel for a later post.

A few months after the above photo with the new dashboard tacked in place, we turned attention briefly to whether the dashboard should receive a wood grain treatment or be painted. I once had a chrome dashboard in a ’32 Ford–bad idea. The glare from the sun nearly blinded me on several occasions. So chrome was out but what about a modern wood grain application? As the wood grain application is basically a decal we gave that a trial run. I liked the off white color much better.

A few months after the above photo with the new dashboard tacked in place, we turned attention briefly to whether the dashboard should receive a wood grain treatment or be painted. I once had a chrome dashboard in a ’32 Ford–bad idea. The glare from the sun nearly blinded me on several occasions. So chrome was out but what about a modern wood grain application? As the wood grain application is basically a decal we gave that a trial run. I liked the off white color much better.

Painted here in the contrast color, Pepper White, the dash really comes alive. I can’t wait to see it after the gorgeous speedometer fills the big center hole and the matching clock takes its position on the glove box door.

And here it is! Now with a few more gauges and big speedometer and clock installed. The project will take a leap forward when the dash is installed in the cab enabling the complex wiring to begin.

The dashboard has continued to be both an inspiration and a frustration. It is truly a gorgeous design, in my opinion, and well worth the extraordinary effort that we’ve put into it. But, at the same time, I would be less than candid to not admit that it has also been complex and costly. And well over a year after the 1935 sedan dash was located, purchased and shipped off to Ralph, it is still not quite complete. In the photo below (January 2018) the dash is in the vehicle with wiring to gauges more or less

complete. Notice that the steering column runs through the dash, not below it. We are using a “Steer Clear” chain device that allows a more horizontal path for the steering column. The windshield crank is also now visible as is the ignition switch to the far left. The two AC vents are functional and both heat and cool air will enter the cab through the dash. The glovebox is not functional although it was originally. We had to seal it as there is no room behind it for a box of any useful depth.

complete. Notice that the steering column runs through the dash, not below it. We are using a “Steer Clear” chain device that allows a more horizontal path for the steering column. The windshield crank is also now visible as is the ignition switch to the far left. The two AC vents are functional and both heat and cool air will enter the cab through the dash. The glovebox is not functional although it was originally. We had to seal it as there is no room behind it for a box of any useful depth.

Finally, the steering wheel is added. This particular wheel is still somewhat uncommon in hot rod use and that suits me fine. It is from Johnson’s Hot Rod Shop and follows a design that was found in the early 20’s. The modern 16″ incarnation is constructed to be adaptable to an Ididit Steering Column. The rim is black and compliments the black and white interior color theme. Being flat offers no protection for the driver in an accident but contributes to a bit more interior room.

Then, almost as an afterthought, we were reminded that the Air Conditioner control knobs had to be mounted somewhere. And out of sight, I instructed, because AC wasn’t available in cars in 1935 and also because these rubber knobs just don’t work with the type of theme we have going. Okay, so I can’t name exactly what theme I think this is but it wouldn’t accommodate two rubber AC knobs. They had to be accessible but out of site.

I gave Ralph a bunch of ideas but they were all either too complicated or wouldn’t fit the available space. In the end, he made a little bracket underneath the dash just to the left of the speedometer. Yes, they will be a little hard to see down there and that is mostly good. I will just have to learn the right positions.

The handmade 16″ steering wheel came with an uninspiring horn button. I found an old Dodge Brothers hubcap (hubs were small in the 20’s) and had Ralph trim it to fit the opening in the wheel for the horn button. We will paint it before long but I am liking this small detail.

The dash is now almost complete. There is a ton of wiring that goes behind it. As soon as that is all in place, Ralph will try to fire up the old baby hemi for the first time.

35 Dodge pickup—not mine but a good one. It shows some factory design effort to please the eye but is frankly quite utilitarian. And that’s generally okay with pickup owners. However, that very same year Dodge had a more visually pleasing dash for buyers of its upscale sedan models. I found one.

35 Dodge pickup—not mine but a good one. It shows some factory design effort to please the eye but is frankly quite utilitarian. And that’s generally okay with pickup owners. However, that very same year Dodge had a more visually pleasing dash for buyers of its upscale sedan models. I found one. This was more like it and I decided to jettison the original dashboard in favor of something with more “dash” and “flare”. I had scoured the country for a Dodge sedan dashboard. This is quite easily done online. I found a parts yard (we used to call them “junk” yards) that had acres of mostly Dodge, DeSoto, Chrysler and Plymouth cars. A sedan dashboard in good shape was on offer. There was no glove box door but I reasoned I could find one elsewhere. And eventually I did, albeit with some difficulty and for a princely sum.

This was more like it and I decided to jettison the original dashboard in favor of something with more “dash” and “flare”. I had scoured the country for a Dodge sedan dashboard. This is quite easily done online. I found a parts yard (we used to call them “junk” yards) that had acres of mostly Dodge, DeSoto, Chrysler and Plymouth cars. A sedan dashboard in good shape was on offer. There was no glove box door but I reasoned I could find one elsewhere. And eventually I did, albeit with some difficulty and for a princely sum.

A few months after the above photo with the new dashboard tacked in place, we turned attention briefly to whether the dashboard should receive a wood grain treatment or be painted. I once had a chrome dashboard in a ’32 Ford–bad idea. The glare from the sun nearly blinded me on several occasions. So chrome was out but what about a modern wood grain application? As the wood grain application is basically a decal we gave that a trial run. I liked the off white color much better.

A few months after the above photo with the new dashboard tacked in place, we turned attention briefly to whether the dashboard should receive a wood grain treatment or be painted. I once had a chrome dashboard in a ’32 Ford–bad idea. The glare from the sun nearly blinded me on several occasions. So chrome was out but what about a modern wood grain application? As the wood grain application is basically a decal we gave that a trial run. I liked the off white color much better.

complete. Notice that the steering column runs through the dash, not below it. We are using a “Steer Clear” chain device that allows a more horizontal path for the steering column. The windshield crank is also now visible as is the ignition switch to the far left. The two AC vents are functional and both heat and cool air will enter the cab through the dash. The glovebox is not functional although it was originally. We had to seal it as there is no room behind it for a box of any useful depth.

complete. Notice that the steering column runs through the dash, not below it. We are using a “Steer Clear” chain device that allows a more horizontal path for the steering column. The windshield crank is also now visible as is the ignition switch to the far left. The two AC vents are functional and both heat and cool air will enter the cab through the dash. The glovebox is not functional although it was originally. We had to seal it as there is no room behind it for a box of any useful depth.

Some holes are filled in, usually because of metal rot, but sometimes because a change will be made and to make everything fit just rust, some basic changes in the body or sheet metal have to be made.

Some holes are filled in, usually because of metal rot, but sometimes because a change will be made and to make everything fit just rust, some basic changes in the body or sheet metal have to be made.

Ralph tried to do it artistically, this time gave the recess a simpler, smoother look. This preserves excessive intrusion into the cab’s interior while allowing us to cram that engine into its new home under the hood of an old Dodge truck.

Ralph tried to do it artistically, this time gave the recess a simpler, smoother look. This preserves excessive intrusion into the cab’s interior while allowing us to cram that engine into its new home under the hood of an old Dodge truck.

Now we ready for the suspension.

Now we ready for the suspension.

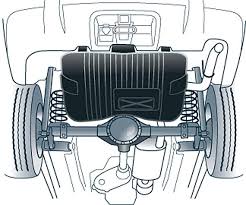

None of the suspension works well for a vehicle with triple the horsepower of the original and with speeds that are at least double those of 1935.

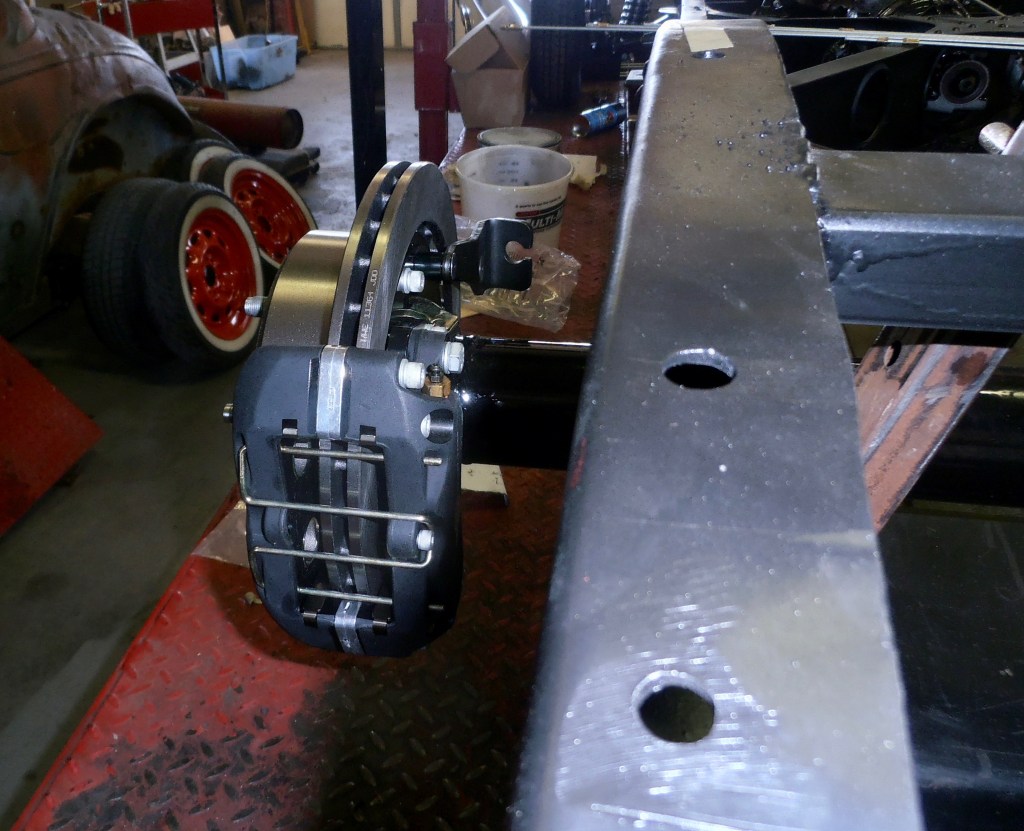

None of the suspension works well for a vehicle with triple the horsepower of the original and with speeds that are at least double those of 1935. The entire suspension system is now new on the ’35 Dodge. It is all painted, and can actually roll around the shop floor. For the front suspension, we used a suspension system from Kugel. They’ve been around a long time. Ralph sends the exact measurements of the frame and other details and they send a kit with parts that bolt on. Some things are welded for safety. Everything is there, breaks, springs, shock absorbers, steering. It saves tons of time, and the ride will be smooth and safe.

The entire suspension system is now new on the ’35 Dodge. It is all painted, and can actually roll around the shop floor. For the front suspension, we used a suspension system from Kugel. They’ve been around a long time. Ralph sends the exact measurements of the frame and other details and they send a kit with parts that bolt on. Some things are welded for safety. Everything is there, breaks, springs, shock absorbers, steering. It saves tons of time, and the ride will be smooth and safe. The pieces come in a box and Ralph welds the several bits to the rear axle housing. Not shown are the very cool coil over shock absorbers.

The pieces come in a box and Ralph welds the several bits to the rear axle housing. Not shown are the very cool coil over shock absorbers.

When I was back in the visualizing stage, I considered many options for the power plant. Almost anything would work. There were several options that would have provided more power for less money and were naturally tempting. But this pickup is a Dodge and, as it turns out, Dodge, a division of Chrysler, made its own small (241 and 270 cubic inch) version of the famous “hemi” engine. The orange one shown in the header is big one. Mine looks the same just in three-quarter scale.

When I was back in the visualizing stage, I considered many options for the power plant. Almost anything would work. There were several options that would have provided more power for less money and were naturally tempting. But this pickup is a Dodge and, as it turns out, Dodge, a division of Chrysler, made its own small (241 and 270 cubic inch) version of the famous “hemi” engine. The orange one shown in the header is big one. Mine looks the same just in three-quarter scale.

In the end I have a visually stunning, better ‘n new Dodge engine. I wish I had a dummy engine, too, made out of foam, that Ralph could use for dozens of trial fits. He has to be so careful using this one and it is so heavy! But it was all I could do to get this far. How powerful is this engine? Maybe 225 to 250 horsepower. Not much you say and you’d be right. But then, yeah, it’s a hemi!

In the end I have a visually stunning, better ‘n new Dodge engine. I wish I had a dummy engine, too, made out of foam, that Ralph could use for dozens of trial fits. He has to be so careful using this one and it is so heavy! But it was all I could do to get this far. How powerful is this engine? Maybe 225 to 250 horsepower. Not much you say and you’d be right. But then, yeah, it’s a hemi!

a “good” and doable and affordable idea. You should be able to see the car in your mind’s eye down to some pretty fine detail.

a “good” and doable and affordable idea. You should be able to see the car in your mind’s eye down to some pretty fine detail.